Blog > State of Michigan Approval of Grant for Copperwood Mine Reveals Rifts in the Environmental Movement and the Need for Dialogue

State of Michigan Approval of Grant for Copperwood Mine Reveals Rifts in the Environmental Movement and the Need for Dialogue

By Brian Noell, Communications Director, YDWP

On Tuesday, March 26, the Michigan Strategic Fund board voted unanimously to approve a $50 million grant to Canadian-owned Highland Copper to aid in development of a sulfide mine adjacent to Lake Superior and Porcupine Mountain State Park. Although the result was not unexpected, it and the subsequent public relations effort are revealing, and, in our view, important to share with Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve supporters. There is pressure at the highest corporate and governmental levels to establish a domestic supply chain for metals deemed of vital importance to the so-called green economy. That push may result in an attempt soon to establish another sulfide mine in our own neighborhood.

Thanks to the efforts of the grassroots coalition assembled in opposition to the grant, the members of which spoke eloquently at the March 26 and February 27 meetings as well as in writing, the MSF board attached significant conditions to the award. The money is to be paid out as a reimbursement, not an outright gift, and only applies to Highland Copper itself (unless MSF gives its consent), ensuring that the company does not pocket the money and abandon the project to another entity. Moreover, there is an infrastructure construction requirement and an obligation to create jobs (yet to be determined, though press releases are touting 380 as the number). Both provide a level of accountability to the local community that might not have existed had activists not pointed out the speculative nature and generally negative net economic effects of mining development in rural America.

Most importantly, MSF is requiring Highland Copper to raise $150 million before the state money is disbursed, a significant hurdle for a company whose valuation is presently less than the $50 million grant itself. Indeed, the company has owned Copperwood for 10 years and already has successively pushed back construction timetables because of undercapitalization.

Also instructive is the public relations exercise that followed the grant announcement. The unanimity of business groups, Northern Michigan University, local government, state representatives, and the Governor herself, was touted in press releases. Job creation, infrastructure improvement, economic development, and securing resources for electric vehicles and other technologies (ideally to be built in Michigan) were in the forefront. Although there will be an undeniable short-term economic impact if the project clears all the monetary and regulatory hurdles it faces and manages to produce ore, one can question the actual number of jobs for locals the mine will create as well as the sustainability of the development an operation predicted to produce only for 11 years will bring. And what about the market for copper itself, which is notoriously volatile and will largely determine the level of ore production, a common phenomenon that results in the type of “flickering” that keeps traditional mining communities in perpetual want?

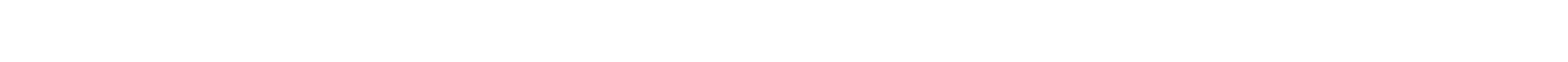

Official press releases and local media coverage of the grant announcement were unquestioningly cheery and, even when mentioning opposition, omitted the substance of those objections. Extraction beneath Porcupine Mountain Wilderness State Park and potentially within 100 feet of Lake Superior itself, for example, as well as construction of a 323-acre tailings facility perched on a slope leading to the big lake and in view of the North Country Trail, Lake of the Clouds Overlook, and Copper Peak were passed over in silence.

The roll-out of the MSF grant is illustrative of a crossroads being approached in the environmental movement, when destruction of wild lands adjacent to a lake containing 10% of the world’s fresh water and an iconic state park is justified in the name of green energy, central to keeping the economy humming in the age of climate change. Political coalition-building underpins the project, which dovetails nicely with conservative priorities to rebuild extractive industries and provide jobs in a region suffering economic hardship and decades of population decline.

From a political perspective, this is a winning strategy for both sides and even seems like a path out of our climate dilemma. But what are the costs? Green energy is not green if the result is the fouling of the world’s largest body of fresh water, which also is vital to addressing the effects of climate change. And what of the more sustainable recreation economy that the MSF’s own bosses, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, are also pushing in their “Pure Michigan” campaign?

Perhaps most importantly, the mainstream narrative that celebrates sustainability, prosperity, and green energy in connection with the development of Copperwood ignores the burden future generations will bear from mineral extraction on the banks of our largest great lake. Maintaining decaying infrastructure and preventing the release of the accumulated waste into Lake Superior will be this project’s longest legacy, adding more than 30 million tons of toxic material to the already steep bill of climate change itself.

Green energy, it turns out, is fraught with trade-offs. For now, however, state and corporate PR apparatus have the information advantage, working hand-in-glove with a local media lacking the resources and perhaps inclination to question the rosy picture being painted for them of “environmentally friendly” industrial projects.

It appears to fall to our organization, and others like us, to put these questions before our supporters and to do some tough thinking about the costs of the “green” economy’s rapid growth. If we begin to see the problem in a multi-faceted way, perhaps a path forward will emerge that includes in the calculus even the effects of our actions on behalf of a warming planet.