Blog > Digging for Truth: Non-ferrous Metallic Hardrock Mining on the Yellow Dog Plains and Recent Permit Changes

Digging for Truth: Non-ferrous Metallic Hardrock Mining on the Yellow Dog Plains and Recent Permit Changes

A recent public hearing on the new draft Groundwater Discharge Permit for Lundin Eagle Mine has once again brought to light the ongoing industrial activity on the Yellow Dog Plains. The hearing took place on March 25, 2014 at Ishpeming Westwood High. The complex saga behind the permitting of this project and the present interface between the nickel/copper mine and the public has created an undeniable divide in our local community, with clearly opposing parties. Ore-extraction has not yet begun, and results from Superior Watershed Partnership’s Community Environmental Monitoring Program show 108 exceedances to-date in the groundwater[i] without a single permit violation from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Discussions about those results are rapidly unfolding and new data continues to be collected and revealed to the public. By law, the mine is required to renew the permits every five years and that time has come. Members of our community are apprehensive about the conditions of this new draft Groundwater Discharge Permit, and concerned organizations influenced the MDEQ Water Resources Division to extend the public comment period and hold a public hearing which is not strictly required. The primary revisions in the new permit will raise site-specific background concentrations for pH and Vanadium, recalibrate the operational range for specific conductance, and add a procedure for reporting Uranium concentrations. About 150 people of all ages and backgrounds attended, and an overwhelming majority of the attendees were not satisfied with the revisions and demanded a stricter statute. This story is not new, it is the most recent development in a ten-year-long regional debate concerning the project and associated risks to human health and the environment.

Let us briefly review the history.

Non-ferrous metallic hardrock mining, or sulfide mining, has caused environmental and financial problems all over the world, such as: degradation of drinking water supplies, loss of natural habitat for fish and other wildlife, company bankruptcy, and abandoned contaminated sites. Knowing this, Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve (YDWP) and Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC) collaborated quickly in 2004, and began monitoring baseline surface water quality conditions on the Yellow Dog Plains prior to any mining activity (except exploration). A surface water quality database has been created for comparison, and ultimately for use in court if necessary. YDWP and KBIC contracted natural resource chemists to conduct regular sampling at 14 sites including spring locations that feed directly into the Salmon Trout River from 2004 to 2012. The springs are the first place possible groundwater contaminants from Eagle will appear in surface water. However, a 2-3 year delay is anticipated. By late 2012, the gold standard in monitoring was secured when this program was transferred to the U.S. Geological Survey in a Cooperative Water Agreement with the tribe. The USGS will continue to monitor the Yellow Dog Plains at many of the original sites for four years from 2013 to 2016 and a report will be released with their findings in 2017. The Superior Watershed Partnership is also monitoring the mine, and through the Community Environmental Monitoring Program they are inside the gates collecting samples to monitor surface water, groundwater, air quality, wildlife and plant life. Funding for the CEMP comes from Eagle Mine and is transferred to the Superior Watershed Partnership (SWP) through the Marquette County Community Foundation. The variety of monitoring activities taking place help us understand the issues, but even unbiased sample collection and EPA-certified lab results cannot stop pollution without the legal system.

Looking back to February 2006, the process of permitting the Eagle Mine project instigated numerous lawsuits from the beginning and the legality of the original permits remains contested to this day. Kennecott Minerals (purchased by Lundin Mining) applied for five permits: Air Discharge, Groundwater Discharge, Mining, Land Use Lease, and Exploration Lease. The MDEQ deemed the application complete after ten days of reviewing 7000 pages. The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) took the issue to court arguing that the MDEQ skimmed over the application. During the court process, the MDEQ issued a list of 91 technical deficiencies in the application to Kennecott. After two court cases and one appeal, the legal system found that NWF was not aggrieved by the situation, allowing Kennecott to move forward. The company replied to the deficiencies and a public commenting session was held. Over 700 community members spoke in opposition to the mining prospect, and referenced issues ranging from the application to the engineering design of the mining facilities. Despite the opposition, by July 2007 the MDEQ issued preliminary approval, and by December 14, 2007 final permits were granted. Immediately following and in response, Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve, National Wildlife Federation, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, and the Huron Mountain Club filed two contested cases and one lawsuit against the MDEQ. The basis of the injunctions is that MDEQ granted approval to an application that did not meet the criteria of Part 632 the Michigan Non-Ferrous Metallic Mining Law. In other words, the four co-petitioners maintain that the permits are inadequate and illegal, and the final verdict is still up in the air and awaiting a date for oral arguments in the Michigan Court of Appeals which agreed to hear the case in August 2012.

Today, it is clear that the 2007 groundwater permit standards set by the MDEQ are not suitable to regulate groundwater quality, and Eagle Mine LLC would likely agree. With 108 exceedances of these limits, the Eagle Mine website Q&A states that vanadium and pH levels were in excess of the permit limits in the monitoring wells. When asked if it is true that Eagle has violated its current permit the answer is, “Eagle has never received a Notice of Violation from state regulators”[ii]. Groundwater monitoring wells were installed by Eagle Mine contractors in 2008 on and surrounding the site to measure baseline or “pre-mining conditions.” This baseline data was collected on a monthly basis from May through October 2008 and on a quarterly basis from January 2009 until October 2011. The mine began to collect operational monitoring data when the wastewater treatment plant began operation in October 2011 which continues today. At the public hearing on March 25, a large portion of the comments and questions addressed the exceedances in groundwater compliance wells. The baseline standards for pH and Vanadium will be increased in this new draft Groundwater Discharge Permit. During the presentation before the hearing, the MDEQ responded to the statement that the proposed permit relaxes the standards for pH and Vanadium, and stated that the exceedances are due to naturally occurring conditions. The MDEQ stated at the public hearing that some wells were not installed when the first permit was developed, and background was assumed to be zero so the permit limit was created halfway between zero and the Part 201 generic residential clean-up standard. Pre-discharge data is now being used to set the new background limits. This procedure is in accord with the state-level rules, but many citizens argue against the rationale behind changing baseline limits at a mine site which has clearly already altered natural conditions. Surface facilities were last reported to be 80% complete and there are more than two miles of underground tunnels,[iii] some of which are below the Salmon Trout River.

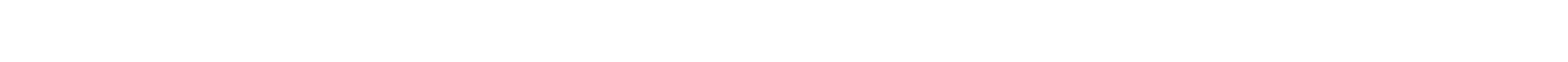

Of the 150 who attended, dozens of citizens at the public hearing spoke about the baseline limits and groundwater hydrology concerns. The public was encouraged to attend, learn and speak due to courageous and effective motivating efforts by Save the Wild UP. Catherine Parker of Marquette has followed the situation for years, and remarked, “The composition and quantity of the water to be treated and ultimately discharged by the Waste Water Treatment Facility at Eagle Mine have not been determined with any degree of certainty. Neither has the behavior of the groundwater, both discharged and naturally occurring. Eagle’s groundwater discharge permit should not be reissued until these concerns have been resolved.” Carla Champagne of Big Bay pointed out missing information in relation to groundwater hydrology and said, “First, the limits set in this permit should be based on the data in Rio Tinto’s 2004 Environmental Baseline Study Stage 1 Hydrology Report. […] Also, since there has never been a complete hydrology study of the region surrounding the mine site, the assertion that all water flows to the northeast is not necessarily proven.” Gene Champagne, also of Big Bay stated, “If certain contaminants are over the limit due to inaccurate baseline data as the MDEQ and Lundin contend, then the entire permit needs to be held up and mine start up delayed until a completely accurate and independent baseline and hydrology study can be completed. If faulty baseline was presented by the mining company and accepted by the DEQ, the public should not have to pay the price with their health and safety.” The MDEQ indicated that further changes to the draft permit may be considered.

Our community members are concerned about the regulatory process for permitting the only primary nickel mine in the U.S.A. which, if miscalculated, poses a real threat to human health and the environment. This project has not yet extracted any ore, and it is expected to begin production in the fourth quarter of 2014, assuming the transportation route from the mine to the mill is complete. With the legacy of contamination from non-ferrous metallic hardrock mines as a precedent, and the incomplete baseline conditions as one of the current crises, not to mention the recent patent infringement case related to the Eagle Mine waste water treatment plant[iv], we anticipate significant issues to arise throughout the operation of this mine and afterwards.

Community Environmental Monitoring [i] www.cempmonitoring.com

Eagle Mine [ii] www.eaglemine.com

End of the Tunnel – Mining Journal [iii] http://www.miningjournal.net/page/content.detail/id/587493/End-of-the-tunnel.html?nav=5006

Lundin Sued in Patent Infringement Case – Mining Journal [iv] http://www.miningjournal.net/page/content.detail/id/596370/Lundin-sued-in-patent-infringement-case.html?nav=5001